Fairview, Alberta, Canada, 28 november 2025 (IICA). On his farm in Fairview, a small town in northern Alberta, Canada, Mackenzie Fingerhut not only grows wheat, barley, oats and flax, but also comes up with ideas, transforms processes, conducts research, takes risks and builds the future, all before even turning 25.

A third-generation farmer, farming alongside his parents and sister, Fingerhut, inspired by the past work of both his grandparents and parents, combines the experience he has inherited with state-of-the-art tools, a regenerative approach and an obsessive pursuit of efficiency, making him a leading figure in Canadian agriculture. His approach to agricultural production, which involves environmental protection, vertical integration and value adding, has garnered the attention of public agencies, fellow farmers, entrepreneurs, and the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA).

IICA has named Fingerhut a Leader of Rurality of the Americas in recognition of his work as a producer, entrepreneur and innovator committed to sustainability. He will receive the Soul of Rurality award, created by the international organization to highlight those who are leaving their mark in support of food and nutritional security and sustainability in the region and the world.

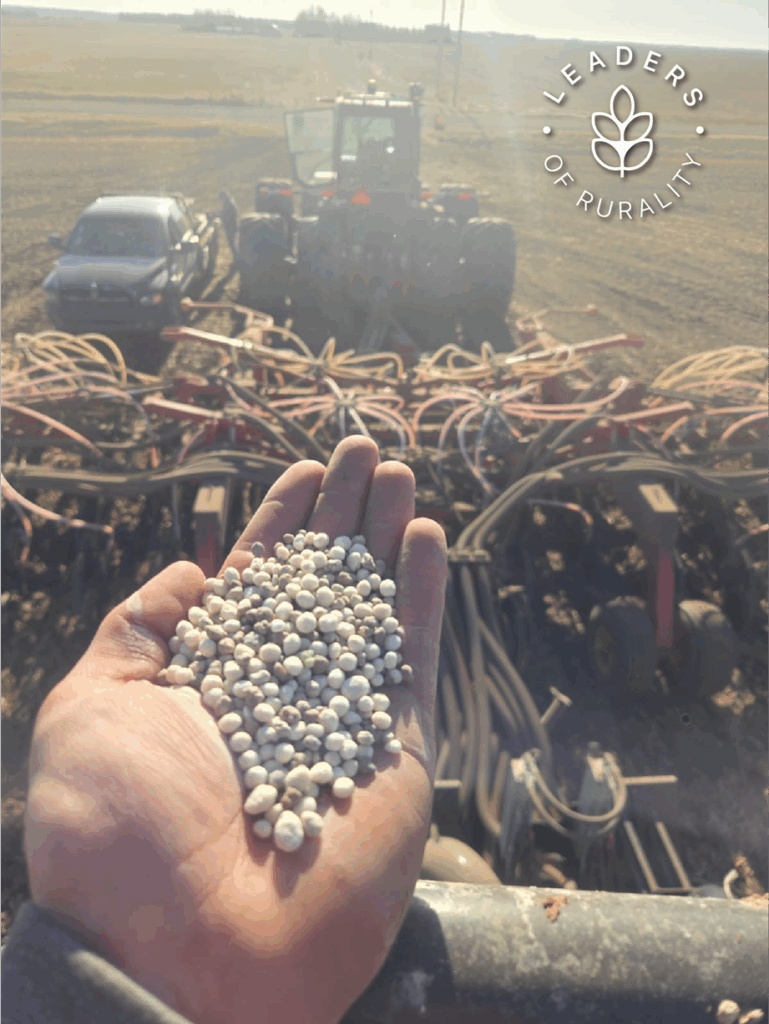

“What we want is to produce more nutritious food, in a closed system, with as little impact as possible and value adding at the source”, explains Fingerhut, who leads an agricultural operation that includes cereals, oilseeds and legumes such as flax, canola, peas and lentils, as well as experimental crops such as corn and sunflowers, which are not as common in that region due to its climate.

In addition to agricultural activity, the farm has an on-site processing plant to extract flaxseed and canola oil and use by-products as a source of high-protein animal feed, aiming for 100 percent efficiency largely inspired by a neighboring farm with its own unique. It also has a line of regenerative inputs that combines phosphorus, sulfur, potassium and compost to nourish soil and reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers, all with locally sourced raw materials and innovative logistical systems.

“The greatest challenge is logistical”, acknowledges Mackenzie, whose facility is located far from major urban centers and Canadian ports. “That’s why”, he adds, “it’s key to transform at the source and make transportation more efficient, while controlling waste and maximizing the use of each by-product”.

A culture of sustainability

For Fingerhut, soil is at the heart of everything. “Our greatest asset is organic matter”, he says. “Caring for the earth, understanding how it behaves and how it interacts with water, nutrients and microorganisms—that’s what ultimately defines system performance and resilience”.

For years, his work has focused on preserving and improving soil through crop rotation, direct seeding, biological inputs and continuous analysis to determine water infiltration levels, biological activity and carbon content. In fact, his experience is part of a pilot project led by Carbon Asset Solutions together with IICA, aimed at measuring carbon.

“What’s interesting is these are not just estimates, but accurate data repeated over time, which allows for verifying how each practice influences carbon capture and soil productivity”, explains the grain and oilseed producer.

This comprehensive and systemic approach is enhanced through the application of state-of-the-art technologies: moisture probes, texture scans, real-time analysis platforms, prediction algorithms and high-resolution drones. “We use both cutting-edge technology and basic field tools. One does not replace the other; instead, they complement each other”, stresses the young Canadian.

“Regenerative”, but avoiding idealism

Fingerhut prefers not to pigeonhole his production model using rigid terms. “For me, regenerative means that a system will be better tomorrow than it is today; that every action seeks to improve soil health, efficiency and sustainability over time”, he explains. “It’s not about applying a formula: some things work and others don’t, and you have to be willing to try, make mistakes and correct them”.

In fact, he recalls that some trials involving mixed crops or extreme input reduction did not yield the expected results. “The important thing is to have a solid technical framework, to measure, compare and make decisions based on agronomic, economic and logistical criteria”, he emphasizes. “And to be patient: some results can be seen in one season, but others take five or six years”.

Fingerhut states that “caring for the land, understanding how it behaves and how it interacts with water, nutrients and microorganisms—that’s what defines system performance and resilience”.

Young people, the city and the beauty of the countryside

A graduate of the prestigious Olds College of Agriculture & Technology, also in Alberta, Mackenzie believes that his generation has a lot to contribute, noting that “young people bring a different mindset, one that is more open to change, new technologies and collaborative work”. Often, he points out, “we have to question practices that have been done the same way for thirty years and propose alternatives that can have a huge impact on performance and sustainability”.

However, he admits that access to land, machinery and inputs is a major obstacle for new producers. “The cost of entry is extremely high, which forces us to be creative, seek out partnerships, develop new business models, or carry out work on a smaller, more intensive scale”, he explains.

In that regard, he believes there are a lot of opportunities for urban youth. “It’s so much more than just driving a tractor. There is room to produce food in controlled environments, to work in technology, logistics and communication. We have to break the stereotype that agriculture only involves grains and cows”, he says.

One of the challenges he is most passionate about is closing the gap between rural and urban areas. “There is a huge disconnect”, regrets Fingerhut. “A lot of people have never seen how food is produced, and that influences their decisions as consumers”.

That is why he is betting on traceability and transparency. “There are projects that enable you to scan a QR code on a bag of flour or a bottle of beer to see the product’s entire history: where its ingredients were grown, how it was processed and who produced it”. He considers that tools of this nature “build trust”.

He warns, however, that they “also require maintaining quality at every step. One bad experience can undermine the efforts of many”.

As for everyday life in the countryside, Fingerhut says it involves “the usual hustle and bustle of any agricultural operation, but it varies a lot”. All you need, he adds, is “flexibility to be able to tackle each day, because you never really know what it will bring”. Rather than viewing it as an obstacle, the young Canadian says one of his favorite parts of life in the countryside is “that there’s a new challenge every day”.

Does he long for anything cities offer, hundreds of miles away? Mackenzie acknowledges that “you often have to create your own fun”, so “inevitably, everyone plays many different sports” in the area, whether it’s hockey, volleyball, track, basketball or badminton. “A lot of different sports that keep us entertained” and, incidentally, build a sense of community.

“No two days are ever the same”, he adds. “There’s always a new challenge. But there’s also tremendous freedom, a sense of community and a connection to nature that I wouldn’t trade for anything else”.

To complete the experience, in the month of July when wheat is already sprouting and canola is in full bloom in his region, the sun can set as late as 11 p.m. “You can’t ask for a better postcard than that”, he says with a smile. “And if you know that you’re doing things right, that what you grow is better for the soil, for the environment and for people, then (all the effort) is worthwhile”.

On his farm in northern Alberta, Canada, Mackenzie Fingerhut grows wheat, barley, oats, flax, peas and lentils

More information:

Institutional Communication Division.

comunicacion.institucional@iica.int