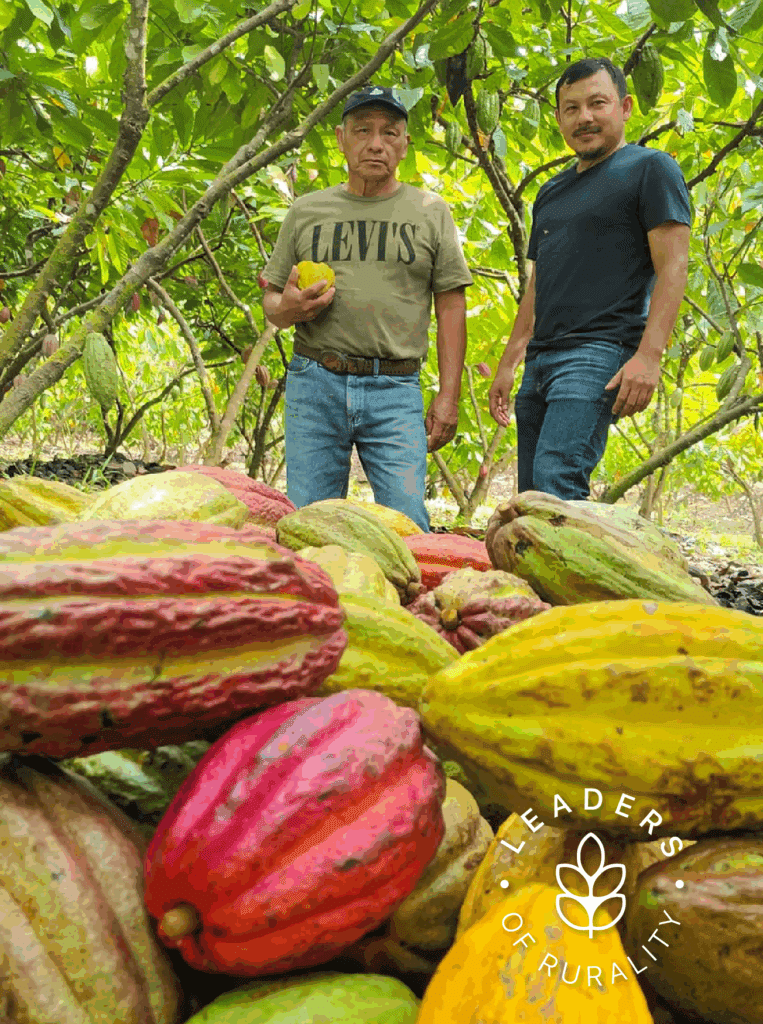

San Jose, 10 September 2025 (IICA) – Erick Geovany Ac Tot—a prominent Guatemalan cocoa entrepreneur who has been assisting small farmer organizations, promoting high-quality cocoa production and preserving heirloom trees for years, in addition to being a cocoa taster—has been named a Leader of Rurality of the Americas by the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA).

In recognition of his work, Ac Tot will receive the “Soul of “Rurality” award, which is part of an IICA program that seeks to turn the spotlight on men and women who are making a difference and leaving their mark in the rural areas of the hemisphere, and in turn playing a key role in regional and global sustainability and in food and nutritional security.

Erick begins by telling us that, “My two unusually short last names reflect my indigenous Q’eqchi Mayan origin and the Alta Verapaz region of northern Guatemala where I was born and raised”. With this he leaves no doubt as to his close ties to the land and legacy of those who were already cultivating and consuming the highly valued cocoa crop before the conquest and colonization of the region.

Hundreds of years later, Erick operates like a true explorer, tracing and preserving Creole cocoa trees hidden in the often near-impenetrable forests of his country. These trees “grew without anyone planting them” and they are practically identical to the trees cultivated by the Mayas. Yet, his efforts are not prompted simply by a love of adventure. The plants carry the DNA of one of the best cocoa varieties in the world and rescuing them has a direct impact on the quality of the product produced in Guatemala and exported to the most discriminating chocolate markets.

It all started for this producer in a village established by a handful of families migrating from another region in the country, including his grandparents’ family. They came to northern Alta Verapaz in the 1950s, through an agricultural development program introduced by the then government. In the early years, there were only three families settling there, “basically to lease lands to produce corn, raise pigs and cultivate other plants, such as beans”, says Erick.

Over time, the village grew as “other families joined and eventually a cooperative was established, through which they bought land and established small plots”, he noted. Thus, “each family had their own piece of land, where they could grow various crops, including cocoa, which is one of the cornerstones of our current business”.

Ac Tot and other producers and experts continue to search for Creole cocoa trees in northern Guatemala, which over time have carried the genes of the plant that the Mayans domesticated some 3,000 years ago.

Between cocoa and football

Erick was the eldest of seven, and the only one of his siblings to be born in the village. When he was still young, the family moved to Cobán, the administrative center and major city in the department of Alta Verapaz (its beautiful name means “quail” in the Yucatec Maya language), where his father had found a good job. There, Erick was able to study and earned a degree in Agronomy from Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.

Ac Tot recalls that, “I would return to visit my grandparents in the village whenever I could, for example, during end-of-year vacations. I loved it because it was a paradise complete with forests and wild animals, where my family had figured out how to cultivate the land”.

Yet, these years in university could have taken him along a path quite unrelated to cocoa and rural production. Seeking to pay for his studies, Erick began to play professional football. In fact, he tells us he reached as far as donning the jersey of the leading Cobán Imperial team. Ultimately, however, the sport and intrigue of the football business did not win him over. He graduated and quickly began to put into practice the lessons learned in the classroom.

His first job was with a European cooperation program that was carrying out community development projects with agricultural components. Then he worked at the university and finally returned to the community where he was raised to work with another cooperation project, “with a major focus on conservation”, but also on forging relationships with farming communities in the areas adjacent to the national park that graces the Lachúa region.

He spent twelve years with this International Union for Conservation of Nature program, which involved him in the field which is now the area of focus of his current entrepreneurial and development efforts: the cocoa value chain. This work reacquainted him with his earliest years when cocoa was grown in home gardens in his grandparents’ village, using “very traditional methods”, says Erick.

Having “immersed himself in that world”, says the entrepreneur, he then had to acquire further experience and knowledge. Today, he sits at the helm of Guatemala Finest Kakau and Guatemala Cacao Company, while also helping to manage the family farm, which bears the name of his mother, Ana María.

A master class

Ave María focuses on exporting high-quality cocoa and genetic selection. “For twenty-five years we have been selecting trees, taking into account four key factors in the industry: productivity, disease tolerance, compatibility at the time of pollination and the flavor profile”. Erick also continues to work with various small farmer organizations and cooperatives in northern Guatemala, where, according to him, 53% of national cocoa production is concentrated.

He also partners with local and regional organizations, both governmental and non-governmental, to identify cooperation funds that can be invested in these community-based cocoa farmers’ associations, to “improve their production levels, their knowledge of plantation management and post-harvesting, and in some cases, to assist in processing cocoa into chocolate and its byproducts”.

Ac Tot also finds time to devote to a dream job: cocoa taster. He explains that “some samples are not very good”, as he pulls out one of the small containers used by tasters to sample the 100 percent cocoa paste. He explains the process, giving us a veritable master class via Zoom.

It begins with a small quantity of cocoa paste. Tasters then follow a method developed by the international organization, Cacao of Excellence, which is responsible for cocoa quality control. Its standards focus on the size of the bean, moisture and other natural factors. There are also stringent standards for roasting and processing into liquor. When the tasters arrive, they pay keen attention to factors ranging from basic flavors (including bitterness and astringency) and fruit and floral notes.

“You have to identify what you are tasting in the sample and give it a score from 1 to 10”, says the Guatemalan entrepreneur, who points out that “of course, you have to be trained to do this”. He explains that during this training “they ask us to taste any and everything, ranging from excellent samples to things that are awful”. In short, he explains that one way of training your palate is “to keep sampling things wherever you go”.

Ac Tot shares more details about the process. For example, if a sample receives a score of less than 6.9, it is considered to be defective and not suitable for any high-quality products. If the score is close to 7, “this means that it is not a complex sample. It has a cocoa flavor and some complementary notes, but it is not exceptional”. When the score ranges between 8 and 9, then this cocoa “has a great deal of complexity in different types of notes, a flavor that lingers on the tongue and is very pleasant”.

A score of between 9 and 10 is practically unheard of – for a flavor existing only in myths. “I have never seen a score of 10 for cocoa; that would be extremely rare”, he says.

This series of rules does not mean that there are rigid profiles for cocoa, because some tasters and consumers of high-quality chocolate products may or may not have a preference for floral or fruity notes or they may prefer more intense acidity. According to Erick, “market preferences” are also a major factor, that is, what the chocolate manufacturers in Europe, Asia or the United States are seeking to import at a given time.

Past and future

The quest for excellence has taken Ac Tot and other producers and experts in search of other legendary elements, such as the Creole cocoa trees in northern Guatemala, that over time have carried the genes of the plant that the Mayans domesticated some 3,000 years ago. In the case of Erick, his first experience with one of these heirloom trees began when his uncle told him: “Look, my father-in-law has a farm, a small plot that has two trees hidden away in the forest. No one planted them; they are just there”.

After traveling to the “small plot”, Ac Tot and his travel companions walked for three hours to a region with the remains of ancient civilizations. The Guatemalan producer was certain that, “If the Mayas were there, there would be cocoa crops”. It wasn’t an easy trek through the intense thicket, but then they looked up and spotted the characteristic Creole cocoa pods “that were quite unlike any other that we would have seen in these fields”.

They split open one of the pods and found that the seeds were completely white. “It was a very emotional moment, because we thought they no longer existed, and to make matters worse every year more forests were being converted into land for cultivation or pastures for cattle”, said Ac Tot. Since then, he explains that heirloom Mayan cocoa has been found in at least fifteen other locations scattered throughout Guatemala – in Petén, Izabal or Alta Verapaz.

“We georeference the material that we find, document it, take photos and measurements and plant the pods. We already have a clonal garden with this material”.

Looking ahead, Ac Tot reflects on this journey that cocoa has taken since pre-Colombian times to the future of globalization. He shares with us some aspects of his current work: the chocolate factory that he is developing in Cobán along with one of his daughters, the multi-hectare expansion of the Ana María farm and other projects he is pursuing with his siblings, wife and three other children, who are professionals.

He maintains that: “Cocoa is part of our culture, part of our traditions”. In fact, he notes that in the times of the Mayas and Olmeca it was used not only as food and in rituals, but also as currency. It is logical therefore that cocoa has become an element that will spur the development of the Guatemalan economy.

More information:

Institutional Communication Division.

comunicacion.institucional@iica.int